Cockamamie myth? Pie-eyed bear sightings? Not so, says this B.C. wildlife biologist — these creatures of folklore really exist.

“I have seen an animal that defies conventional description.”

So began a letter to me from a resident of British Columbia’s West Kootenay region, describing what he saw on his rural acreage one morning in September 1998. He agreed to provide details if I would assure him complete confidentiality.

Initially, he thought it was his neighbour walking among the shrubs, but says he soon realized the animal was not human. As he caught increasingly good views, he mentally discarded bears, then cougar, as possible explanations.

“One minute this creature was able to squat and be no more than three of four feet in height. The next, it seemed to be able to draw itself up to six feet, or perhaps more in length.” Three others appeared, and one of the smaller ones climbed into the branches of a tree. “It was then that I first had the thought that I was looking at monkeys … The profile was like that of an orangutan. It seemed to have hair not fur.

“The one that… had first drawn my attention drew up behind slightly denser bush and walked off on its hind legs … This really floored me … The movement seemed so naturally bipedal.”

“The one that… had first drawn my attention drew up behind slightly denser bush and walked off on its hind legs … This really floored me … The movement seemed so naturally bipedal.”

After about 35 minutes, all but one of the animals had disappeared into the forest. “It seemed that this would be the last chance to determine … whether I had really been watching bears, I was not disappointed. It, too, finally rose up. I was extremely struck with its barrel chest and seemingly long, skinny legs and arms. This, though, was only relative to its large chest and upper body. It walked off! Maybe two or three strides and it was gone.”

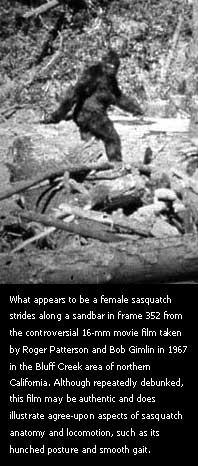

“It most definitely walked erect with shoulders sloped forward. The gait was not like gorillas that I have seen either in the zoos or on TV. Nor was it that peculiar walk of the orangutan. This was a full easy stride.”

“I suppose for me, I must accept that I probably saw sasquatches that day. I keep waiting for a news report that tells me that a private zoo has lost some apes or something similar.”

National political columnist Allan Fotheringham once characterized B.C. as the land of “Social Credit and the sasquatch.” B.C. journalist Stephen Franklin called the sasquatch, “the godsend of newspaper cartoonists in the silly season when politicians are on vacation.” The creature is, as Canadian folklorist Carole Carpenter once said, part of B.C.’s “cultural identity.” Long before our time, the Kwakwaka’wakw people depicted Tsonoqua, “Wild Woman of the Woods,” on West Coast totem poles and masks as a giantess with pursed lips, along with her male counterpart, Bukwuss. The words “sasquatch” itself comes from the Coast Salish term Sasqits, or “hairy man.”

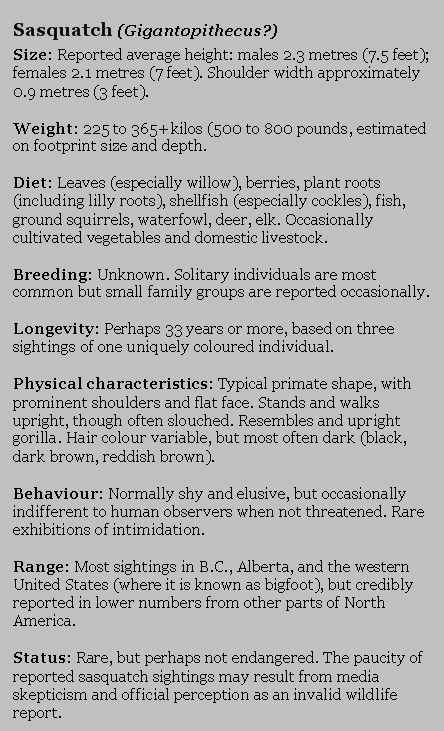

It is my conviction that the sasquatch, or bigfoot, is real, and that its very existence has generated the myths, aboriginal legends, newspaper reports — and yes, the jokes and hoaxes. As a wildlife biologist, I have examined the issues for more than 25 years, and not only do I believe the sasquatch is a real animal but one about which we know a great deal. We have samples of its tracks and scat, and reports of its “eye-watering” odour. We know details of its physical appearance, its diet. and its behaviour in feeding, nesting, and defending its territory.

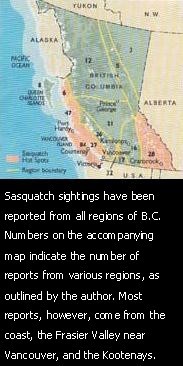

There have been more than 200 reported sasquatch sightings in B.C. alone. Eyewitnesses are remarkably consistent in their basic description of the animal encountered or observed, reporting a large, upright, human-shaped animal standing or walking on its hind legs. The shoulders are prominent, like those of a human, but the neck is short and thick. The animal is covered with hair, usually dark in colour. The arms are proportionately longer than those of a human. Witnesses are often impressed by the animal’s huge size.

In some cases more detail has been observed: a barrel chest (“its chest was as deep as it was wide”), a flat, broad nose (“like a gorilla”), an area of bare skin on the face around the eyes, and the apparent absence of ears, which, if present, were hidden by long hair. Some witnesses say they saw breasts on what appeared to be adult females.

In some cases more detail has been observed: a barrel chest (“its chest was as deep as it was wide”), a flat, broad nose (“like a gorilla”), an area of bare skin on the face around the eyes, and the apparent absence of ears, which, if present, were hidden by long hair. Some witnesses say they saw breasts on what appeared to be adult females.

Despite the compelling consistency of eyewitness reports, most wildlife biologists do not recognize the sasquatch as a valid wildlife species in B.C. or elsewhere. Skeptics remain the majority, and their arguments merit examination. How, they say, could such a large animal exist here without being seen more often? Why do we have no good photographs of a living sasquatch, no bones or teeth of a dead one? How is it no sasquatch has ever been roadkill, or fallen into the sights of a backwoods hunter?

The media’s treatment of sasquatch reports may provide part of the answer. A sasquatch sighting, when reported, normally takes the form of a light-hearted news item, often recounted with a knowing grin and the suggestion that the eyewitness was on the way home from a pub. While a healthy skepticism regarding the existence of an ape-like animal in B.C. is justified, such cynicism and ridicule tend to inhibit other witnesses, such as the West Kootenay man, from coming forward publicly.

John Green of Harrison Hot Springs published The Sasquatch File in 1973, summarizing 110 reported sightings in B.C. He concluded then that animals answering the description of sasquatch are seen far more often than we realize. To date, Green has collected almost 350 B.C. sightings of sasquatches or their tracks — but witnesses remain as reluctant, as fearful of ridicule, as they were 27 years ago.

Nevertheless, those who have seen a sasquatch — especially those employed in outdoor occupations who are familiar with bears — know when they have seen an unusual animal and wish to report it. Balanced media treatment of sasquatch evidence inevitably results in an outpouring of fresh reports.

As for the absence of sasquatch remains — bones, teeth, hair, a body — this is understandable in the case of an uncommon or rare mammal. Wildlife biologists and archaeologists recognize how quickly animal remains are scattered, eaten, and broken down in nature, especially in our acidic B.C. soils. The possibility remains that well-preserved sasquatch bones may yet be found in a limestone cave or similar site.

That sasquatches have escaped roadkill may attest simply to their intelligence in avoiding moving automobiles, and their preference for backwoods habitat. None have been shot, though a few hunters have had opportunity. While hunting deer in the Okanagan Valley north of Vernon on September 11, 1994, Randy Rudnyk says he watched a sasquatch in his rifle scope for almost 15 minutes — never thinking of killing it, though he was close enough to move the crosshairs from eye to eye. In October 1955, William Roe says he levelled a gun at a female sasquatch on B.C.’s Mica Mountain. “If I shot it, I would possibly have a specimen of great interest to scientists the world over,” said Roe. “I lowered the rifle. Although I had called the creature ‘it,’ I felt now that it was a human being and I knew I would never forgive myself if I killed it.”

That sasquatches have escaped roadkill may attest simply to their intelligence in avoiding moving automobiles, and their preference for backwoods habitat. None have been shot, though a few hunters have had opportunity. While hunting deer in the Okanagan Valley north of Vernon on September 11, 1994, Randy Rudnyk says he watched a sasquatch in his rifle scope for almost 15 minutes — never thinking of killing it, though he was close enough to move the crosshairs from eye to eye. In October 1955, William Roe says he levelled a gun at a female sasquatch on B.C.’s Mica Mountain. “If I shot it, I would possibly have a specimen of great interest to scientists the world over,” said Roe. “I lowered the rifle. Although I had called the creature ‘it,’ I felt now that it was a human being and I knew I would never forgive myself if I killed it.”

While we have no body of a sasquatch, we are not without physical evidence of it’s existence. Scat has occasionally been reported where sasquatches have been sighted. William Roe backtracked the female sasquatch he observed on Mica Mountain and dissected several scats, finding only vegetable matter. John Christman of Bremerton, Washington, found a deposit on the Olympic Peninsula “the diameter of a pop can and enough to fill a large bucket.” Unfortunately, it may be that sasquatch scat is not sufficiently different from that of large bears to provide definitive evidence. But then there are the footprints.

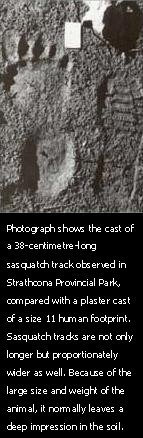

Sasquatch tracks are characterized by their elongated human-like shape, the absence of claw marks, and the occurrence of “hind” feet only. Bear tracks, by comparison, show claw marks, the pointed heel of the bear’s hind foot, and the presence of alternating forefoot and hind foot impressions. Compared to human footprints, sasquatch tracks differ mainly in size: those recorded vary from seven to 22 inches (17 to 56 centimetres), with an average in John Green’s records of 16 inches (40 centimetres). Physical anthropologist Dr. Grover Krantz, author of Big Footprints: a Scientific Inquiry into the Reality of Sasquatch (1992), states that sasquatch footprints are normally one-third wider than human footprints of the same length.

Most mammals are nocturnal or crepuscular (active mainly at night, or at dawn and dusk), and so are observed infrequently. Wildlife biologists routinely accept mammal tracks as evidence than an elusive species is present, without need of a sighting. This is common practice for bears, wolves, and caribou — yet most scientists will not accord the sasquatch the same benefit of the doubt.

Most mammals are nocturnal or crepuscular (active mainly at night, or at dawn and dusk), and so are observed infrequently. Wildlife biologists routinely accept mammal tracks as evidence than an elusive species is present, without need of a sighting. This is common practice for bears, wolves, and caribou — yet most scientists will not accord the sasquatch the same benefit of the doubt.

Nevertheless, laypersons have observed sasquatches engaged in feeding and nesting as other animals do. In some cases the creatures have left physical evidence of their activities. In spring 1997, bear hunter Mike MacDonald observed a sasquatch eating willow buds and young leaves in the Fraser Canyon. To reach buds above its head, it stood upright and pulled the branch tips down to its mouth with one extended arm and hand. In October 1967, in a remote part of Oregon’s Cascade Range, Glen Thomas observed a male sasquatch dig a pit, from which it obtained and ate ground squirrels. Edwin James, along with a group of friends and family members, surprised a sasquatch digging for clams on Gilford Island in the 1950s. A friend of Audrey Wilson of Alert Bay was driving south with her husband near Sayward, Vancouver Island, when she saw a sasquatch dragging a deer up a mountainside beside the highway. Ten minutes later she asked her husband, “Did you see that?” His answer: “Yes. Did you?”

Prospectors, hunters, and biologists from the B.C. coast and Interior have reported sasquatch nests, which differ from bear beds and dens in having a woven rim and sometimes a roof. Dr. Fred Bunnell, a University of British Columbia wildlife biologist described a “sasquatch bower” he discovered with unusual bent and broken branches overarching a nest against a rock face. “No bear makes a day bed like that,” Bunnell concluded.

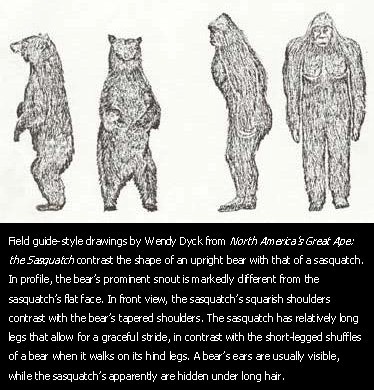

Most biologists assume that eyewitnesses reporting sasquatches are misidentifying upright bears, since a bear on its hind legs is the closest acceptable approximation. Others argue that claimants were duped by tricksters wearing fur suits. Unfortunately, witnesses have had little with which to compare their own observations. The sasquatch is notably absent from our field guides, the authoritative reference books on which we depend to identify the animals of our natural world.

Most biologists assume that eyewitnesses reporting sasquatches are misidentifying upright bears, since a bear on its hind legs is the closest acceptable approximation. Others argue that claimants were duped by tricksters wearing fur suits. Unfortunately, witnesses have had little with which to compare their own observations. The sasquatch is notably absent from our field guides, the authoritative reference books on which we depend to identify the animals of our natural world.

In my recent book, North America’s Great Ape: the Sasquatch, I have included field guide-style illustrations that compare the squarish, human-like shoulders of the sasquatch with the tapered shoulders of the bear. In profile, the sasquatch’s flat face contrasts with a bear’s prominent snout. As well, the distinctive sasquatch gait — a graceful, ground-eating stride with arms swinging — is very unlike the bear’s briefly maintained upright shuffle on its short hind legs. The fluid sasquatch gait also differs significantly from the stiff-legged human gait. The West Kootenay eyewitness quoted above recalled seeing the animals “moving in the trees in a way no human could have imitated without a lot of noise and superb acrobatic training. They would … move rapidly from one place to another with a gracefulness and ease.”

I have studied evidence of the sasquatch since I first found tracks on Vancouver Island in 1988, and my research suggests the sasquatch is, in fact, a great ape. Dr. Krantz proposed that the sasquatch may be the descendant of Gigantopithecus, a giant fossil ape of Asia — or, more likely in his view, actually may be Gigantopithecus, “still with us.” Unlike the great apes of Africa and Asia, however, the sasquatch has a more human-like stride and foot shape.

Occasionally, sasquatches in remote areas have revealed themselves, and their ape-likeness, in their attempt to repel humans. While most sightings involve a sasquatch walking or running away, or watching curiously from a distance, there have been reports of apparent intimidation. While walking up a beach in B.C.’s remote Deserters Group of islands in the early 1990s, some clam diggers sped an animal with an “ape face” watching them from behind a large stump. It then began to throw rocks and driftwood. “A large rock just missed my head!” recalls Samson Cecil, adding that his group then set a possible world speed record for dragging a skiff down a beach into the water.

Campers on beaches and riverbanks have been threatened by the sound of a large animal running back and forth just inside the adjacent forest, vocalizing, breaking large branches, and making a great deal of noise without showing itself fully. When this happened to Mary Strussi and her friend on Vancouver Island’s Cruickshank River in the summer of 1992, they abandoned their tent for the security of their truck. Some years earlier, two men in a truck camper on the west side of Harrison Lake noticed an ape-like face in their window, and immediately afterwards felt their vehicle being shaken “as if that thing wanted to turn us over.”

In general, the sasquatch seems quite benign, with little or no interest in harming people. Its uncommon intimidation displays — breaking branches, running back and forth, throwing stones — are remarkably similar to those of chimpanzees. The result is to drive intruders from the animal’s range, away from its young or a rich food source, without actual physical interaction.

Another interesting parallel to the ape world is the reported persistence of sasquatch odour, described by observers as a “strong stench of rotten eggs” or “rotten meat.” The smell “makes you gag or want to vomit,” said Jo Jo Christianson, a crew member on the seiner Skidegate who caught wind of two shoreside sasquatches near Alert Bay in September 1994. The overpowering odour is likely of glandular origin, as with mountain gorillas, which, according to noted researcher Dian Fossey, emit “a gagging fear odour” when threatened.

Another interesting parallel to the ape world is the reported persistence of sasquatch odour, described by observers as a “strong stench of rotten eggs” or “rotten meat.” The smell “makes you gag or want to vomit,” said Jo Jo Christianson, a crew member on the seiner Skidegate who caught wind of two shoreside sasquatches near Alert Bay in September 1994. The overpowering odour is likely of glandular origin, as with mountain gorillas, which, according to noted researcher Dian Fossey, emit “a gagging fear odour” when threatened.

My interest in the sasquatch often raises eyebrows, but I am not alone in my convictions. I have been encouraged in my research by professional colleagues in the international wildlife research community — researchers not subject to our local and regional conditioning. Jane Goodall, widely known for her pioneering field studies of chimpanzees in Tanzania, admits to a long-time interest in ”’wild men,’ the yeti, bigfoot, and the sasquatch.” She called my book “exciting” and acknowledged my efforts to “carefully describe the behavioural characteristics that have been recorded for the sasquatch.” Dr. Vernon Reynolds, an Oxford University primatologist and author of The Apes, was impressed with “the many points of similarity between sasquatch anatomy and behaviour and that of the great apes.” Biologist Dr. George Schaller, author of Year of the Gorilla, thought I showed “a lot of insight” and made “sensible deductions” in developing my hypothesis that the sasquatch could be North America’s great ape.

I am now convinced that sasquatches are seen far more often than we know. Indeed, some of my professional colleagues in the provincial Wildlife Branch have admitted to being less than diligent in filing sasquatch reports. Yet some witnesses continue to come forward — challenging our collective skepticism, braving public ridicule. As recently as September 1999, a Vancouver youth said he observed a sasquatch near Bradley Lagoon on the B.C. coast.

I fully expect that wildlife biologists will recognize the sasquatch as a species in the not-too-distant future, and subsequent researchers will find B.C.’s shellfish-rich West Coast to be one of its prime habitats. But until other North American biologists are willing to look beyond their own continent for possible explanations — and until we finally have irrefutable evidence that sasquatch exists — doubt will continue to linger, and witness will remain reluctant to speak out.

As the West Kootenay eyewitness mused at the end of his letter: “I think if anybody asks me I might deny the whole thing and cover it up by saying I saw bears and it was a joke.”

John A. Bindernagel Ph.D., is a registered professional biologist in B.C. with more than 30 years of field expertise. He is the author of North America’s Great Ape: the Sasquatch (Courtenay: Beachcomber Books, 1998, Box 3286, Courtenay, B.C.), a field guide to the anatomy, ecology, food habits, and behaviour of the sasquatch.

From: Beautiful British Columbia Magazine, Summer 2000.