Last updated on January 20th, 2021 at 02:08 pm

by Theo Stein, Denver Post, Environmental Writer

Legitimate scientific study of legend gains backing of top primate experts

Sunday, January 05, 2003 — Edmonds, Wash. — After enduring decades of ridicule, Bigfoot researchers are enjoying support from some of the world’s most respected scientists in their efforts to prove the hulking creatures of legend are no myth.

Richard Noll of the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization photographs a site in the North Cascades, northeast of Seattle, last month. Noll and colleagues discovered an imprint near a mudhole where the Skookum Cast was recorded two years ago.

The persistence of reported sightings of Bigfoot-type creatures in North America and elsewhere has convinced leading researchers on primates — including Jane Goodall, made famous by her studies of chimpanzees in Tanzania — to call for something never seriously considered before: a legitimate scientific study to determine whether the greatest apes that ever lived persist in the world’s moist mountainous regions.

Skeptics, who include those in the scientific mainstream, scoff at such ideas. They say reported Bigfoot encounters, tracks and other evidence are either hoaxes or mistakes, and that people who believe such nonsense are soft-headed.

But dedicated amateurs and a smattering of professionals are trying to change that attitude. Using accepted scientific methods, they believe they can show at least some of the claimed evidence for Bigfoot — footprints, hair, voice recordings and a 400-pound block of plaster known as the Skookum Cast — are authentic traces of a rare giant primate.

Recently they have received support from a handful of the field’s top experts.

Daris Swindler, for example, is not the typical Bigfoot believer.

When he retired in 1991 after more than 30 years at the University of Washington, Swindler was an acclaimed expert in the arcane study of fossilized primate teeth.

His book, An Atlas of Primate Gross Anatomy, went through several printings and was among the standard references in the field.

So it comes as a surprise to some of his peers that Swindler believes that the Skookum Cast, discovered by amateur Bigfoot researchers in 2000, is a genuine record of a hairy giant that sat down by a mudhole to eat some fruit.

“Daris said that?” asked Russell Ciochon, a prominent paleoanthropologist and professor at the University of Iowa. “He’s an important figure. But I still don’t think Bigfoot exists in any form.”

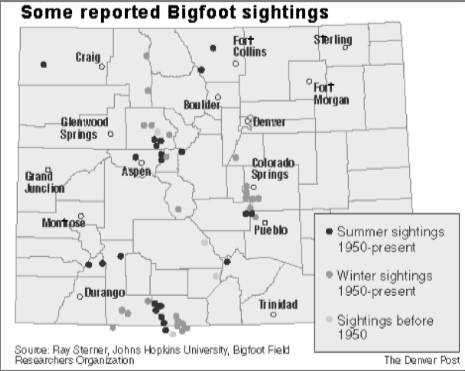

Mythical giant apes lurk in the traditions of nearly every Native American linguistic group and in legends handed down through the ages from Europe and Asia. Each year, Bigfoot or similar creatures are reported by hundreds of hunters, hikers, motorists and others from central Asia to the central Rockies. But no one has provided the minimum proof required by science: a type specimen or remains that researchers can pick up, measure and argue over.

Nevertheless, Goodall is intrigued.

“People from very different backgrounds and different parts of the world have described very similar creatures behaving in similar ways and uttering some strikingly similar sounds,” she said. “As far as I am concerned, the existence of hominids of this sort is a very real probability.”

George Schaller, director of science at the Wildlife Conservation Society, has spent 40 years studying rare animals in remote places, including pioneering studies of Central Africa’s mountain gorilla, which Western scientists first discovered in 1903.

Schaller remains troubled by the fact no Bigfoot remains have been produced, nor have any samples of feces whose DNA can be chemically poked and prodded to unlock the identity of their maker. And he is mindful of hoaxing.

But he, too, considers Bigfoot an open question.

“There have been so many sightings over the years,” he said. “Even if you throw out 95 percent of them, there ought to be some explanation for the rest. The same goes for some of these tracks.”

“I think a hard-eyed look is absolutely essential,” he concludes.

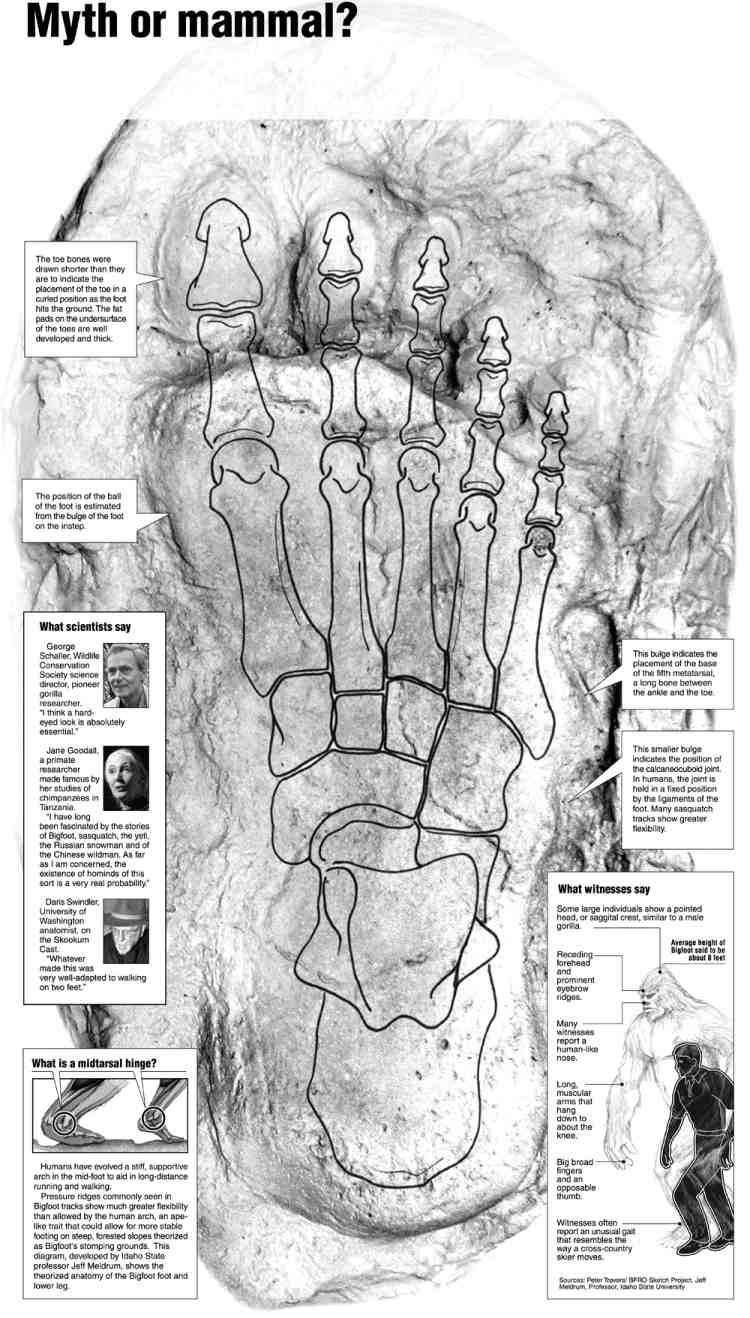

The most common evidence allegedly left by these animals are the footprints: big prints in remote locations, some deeply pressed in sand or gravel firm enough for a grown man to pass without leaving a trace. Some footprints, like those Ray Wallace’s family claim he left near Bluff Creek, Calif., in the late 1950s, are hoaxed. Many more are too vague to be conclusive. But a few are so detailed and anatomically accurate that they baffle the experts.

“Either the forgers are spending an awful lot of time on this, or there is reason to give this evidence another look,” said primate researcher Esteban Sarmiento of the American Museum of Natural History. “I think a serious scientific inquiry is definitely warranted.”

Skeptics argue that large mammals, particularly great apes, simply aren’t discovered anymore. Not true, says Russell Mittermeier, vice president of Conservation International, who has co-authored scientific papers describing five new primates.

Since the 1990s there have been several spectacular finds, he said, including the antelope-like spindlehorn from Vietnam and a South American peccary thought to have gone extinct thousands of years ago.

“I’m not one to pooh-pooh the potential that these large apes may exist,” Mittermeier said. “I guess you could say I’m mildly skeptical but guardedly optimistic. Whoever does find it will have the discovery of the century.”

Words of encouragement like these are music to Bigfoot researchers’ ears.

Some of the world’s top primate researchers say the persistent sightings of Bigfoot-type creatures have convinced them that legitimate research needs to be done. The most compelling evidence of the creatures’ existence consists of footprints, such as the one in this cast of the ‘Heryford Track,’ discovered in Gray’s Harbor County, Wash., in April 1982. Researchers say the print’s width, bulges, shape and other features provide clues to the placement of joints and bone lengths. The sketch and analysis were provided by Idaho State professor Jeff Meldrum.

“My whole motivation has not been to convince anybody of the existence of the animal, but to convince them that there’s a body of evidence begging for further consideration,” said Idaho State University professor Jeff Meldrum, whose expertise in primate locomotion led him to become one of the few academics openly researching Bigfoot tracks.

“This is immense,” said author John Green, who has tracked Bigfoot reports for almost half a century from British Columbia and investigated some of the most famous sightings and track finds. “The possibility that there could be a real animal behind it just didn’t occur to scientists 20 years ago.”

The flap over recent claims of Bigfoot hoaxing has not deterred Swindler. But the lack of a body plus the acknowledgment of at least some hoaxing adds up to too many questions for Ciochon.

Like that of Swindler, Ciochon’s work focuses on fossilized primate teeth, but of a very special species: Gigantopithecus blacki, the giant Asian ape of the Miocene epoch, which lasted from about 24 million to 5 million years ago.

Most Bigfoot supporters advance Gigantopithecus, or Giganto for short, as the likely ancestor of Bigfoot, if not the hairy beast itself. It’s a tantalizing but entirely unproven link that drives Ciochon to distraction.

Ciochon thinks his study subject, which co-existed with the human ancestor Homo erectus for hundreds of thousands of years, may well be the archetypal inspiration for the “boogeyman” and other nocturnal monsters that populate the traditions of aboriginal cultures from Nepal to North America.

But he vigorously rejects any suggestion that Giganto, which he thinks was a specialized, bamboo-eating vegetarian, could persist today.

And he worries that the hotly contested grants that fund his work overseas may go elsewhere if the stigma of the shambling sasquatch of Native American lore attaches to his study subject.

“My biggest problem is there’s no evidence, other than conjectural hair and these footprints, some of which we know are faked,” Ciochon said.

“If someone finds a skeleton, I’ll be there in a nanosecond,” he said. “But that’s what it’s going to take to get me to change my mind.”

“There are so many problems,” agrees Swindler, who six years ago told a USA Today reporter to count him among the skeptics.

But as he examines the Skookum Cast on a rainy December afternoon in this Seattle suburb, Swindler points out landmarks in the lumpy landscape: a hairy forearm the size of a small ham, an enormous hairy thigh, an outsized buttock, and a striking impression he feels confident was made by the Achilles tendon and heel of a creature that is not supposed to exist.

“Whatever made this was very well adapted to walking on two feet,” he said. “It’s not conclusive, but it’s consistent with what you’d expect to see if a giant biped sat down in the mud.”

Swindler hopes that his assessment of the Skookum Cast, and a Discovery Channel documentary set to air Thursday, will generate support for further research.

The key, Schaller said, will be finding dedicated amateurs willing to spend months or years in the field with cameras. “So far, no one has done that,” he said.

It was a group of dedicated amateurs that discovered the Skookum Cast. A team of volunteers from the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization had spent two days in Washington state’s Gifford Pinchot National Forest, putting out pheromone-basted plastic chips during the day and blasting sasquatch calls at night in an attempt to attract an animal.

On the second night, researchers heard a powerful reply to their broadcasts, said Richard Noll, an aerospace toolmaker who has spent 30 years researching the mystery. The next morning, Noll was stunned to realize that an unusual impression of a large animal on the edge of a mudhole near their camp could have been left by their elusive quarry.

“An elk will gather their feet under them when they get up,” he said. “But there are no elk hoofprints in the center of the cast.”

Meldrum and Swindler concur there are only two logical explanations for the cast: Bigfoot and elk. And they have also ruled out elk.

John Mionczynski, a wildlife researcher who has spent 30 summers studying bighorn herds in Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains, has his own reasons for believing in Bigfoot.

On a moonlit summer night in 1972, he backhanded an animal he thought was a bear as it sniffed at a bacon stain in his tent, then watched as the silhouette of a giant, shaggy arm with a broad hand at the end swept toward his tent, collapsing it on him.

“That hand was three times as wide as mine and had an opposed thumb that stuck out as plain as day,” Mionczynski said.

He spent the rest of the night huddled by the fire with a revolver in his hand as the creature lobbed pine cones at him from the dark woods behind his tent.

“That pretty much eliminated bears,” Mionczynski said.

Mionczynski is working on a contraption of tiny hooks and barbed wire that he intends to place near seasonal foods he thinks sasquatch depend on. He hopes the snare will let him get a DNA sample.

North of Seattle, Noll is collaborating with Owen Caddy, a former Ugandan park ranger who studied chimpanzees in the mid-1990s.

For the last 18 months, they’ve scoured certain sandbars on a north Cascades river, documenting more than 30 suspected sasquatch footprints they believe were made by a mother and two young. They hope to identify the animals’ food sources and travel corridors, then set out a picket line of infrared camera traps.

“I feel the animal is out there, and I don’t hedge on that,” Caddy said. “I’ve found physical evidence myself, and I’m confident in my analysis of it.

“Something is making these tracks, and it’s not people.”

The Scientists:

Jane Goodall. A world-famous primate researcher and author, she revealed, in studies of chimpanzees in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park, surprising behaviors in humanity’s closest living relative. Goodall has won numerous international awards for her contributions to conservation, anthropology and animal welfare. Currently affiliated with Cornell University, she serves as the National Geographic Society’s explorer-in-residence.

George Schaller. International science director for the Wildlife Conservation Society. His pioneering field studies of mountain gorillas set the research standard later adopted by Goodall and gorilla researcher Dian Fosse. Schaller’s 1963 book, The Year of the Gorilla, debunked popular perceptions of the great ape and reintroduced “King Kong” as a shy, social vegetarian.

Schaller’s studies of tigers, lions, snow leopards and pandas also advanced the knowledge of those endangered mammals.

In 1973, he won the National Book Award for The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator-Prey Relations, and in 1980 was awarded the World Wildlife Fund Gold Medal for his contributions to the understanding and conservation of endangered species. During the past decade, he has focused on the little-known wildlife of Mongolia, Laos and the Tibetan Plateau.

Russell Mittermeier. A trained primatologist, herpetologist and biological anthropologist, he has discovered five new species of monkey, including two last year. Mittermeier has conducted fieldwork in more than 20 countries around the tropical world, with special emphasis on Brazil, Guyana and Madagascar.

Since 1989, Mittermeier has served as president of Conservation International, which has become one of the most aggressive and effective conservation organizations in the world during the last decade. His publications include 10 books and more than 300 scientific papers and popular articles.

Daris Swindler. Emeritus professor of anthropology at the University of Washington, Swindler is a leading expert on living and fossil primate teeth and one of the top primate anatomists in general. His book, An Atlas of Primate Gross Anatomy, has become a standard reference in the field. A forensic anthropologist, Swindler worked on the Ted Bundy and Green River murder cases along with hundreds of others.

Esteban Sarmiento. A functional anatomist affiliated with the American Museum of Natural History, Sarmiento focuses on the skeletons of hominids. In 2001, he participated with George Schaller in a search for Congo’s Bili ape, a possible species super-chimp reported by natives but unknown to Western science. Sarmiento has also studied the Cross River gorilla, a critically endangered subspecies on the Nigeria-Cameroon border whose population is thought to be numbered in the hundreds. He has taught in the U.S., South Africa and Uganda.

From: The Denver Post, 5 January 2003.