Last updated on August 8th, 2021 at 08:37 am

Most of the information for this section was adapted from material written by John A. Bindernagel, a wildlife biologist from British Columbia, and is used with his permission. Additional regional anecdotal material was provided by the North American Wood Ape Conservancy (NAWAC).

Body Shape

Although the initial impression of the wood ape is its humanlike, rather than bearlike, shape, there are several aspects of its appearance that differ from the human form.

Large Bulk, Powerful Build, and Thick Chest

After registering the initial resemblance to a human, most observers become aware of the large size and overall massiveness of the wood ape. Although difficult to quantify, the wood ape’s powerful build is reflected especially in its broad shoulders and thick chest. William Roe, describing the female wood ape he observed within twenty feet of him, noted that “this animal seemed almost round. It was as deep through as it was wide…” Roe went on to say that “we have to get away from the idea of comparing it to a human being as we know them.” Similarly, the sasquatch Tom Sewid saw in a British Columbia coastal beach in the spotlight of his fishboat in September, 1994, had a chest “like one-and-a-half forty-five gallon barrels.”

Neck

A neck that is absent or is exceedingly short and thick is a consistent field mark, mentioned in many reports. William Roe noted the neck of the one he saw as “’unhuman’, being thicker and shorter than any man’s I had ever seen.” Referring to the adult male he watched for several days, Albert Ostman said that “if the old man were to wear a collar it would have to be at least thirty inches.” One witness described the wood ape he saw as looking like someone in a hooded sweatshirt. Examination of several frames of the Patterson-Gimlin film shows that the apparent absence of a neck in the female wood ape may be due not only to its hunched posture, but also to the extremely well-developed trapezius muscles which extend from the back of the skull well out onto the shoulders. A young man who came face to face with a wood ape near Jefferson, Texas in 1989 as a boy reported that “its neck was very thick and maybe short…”

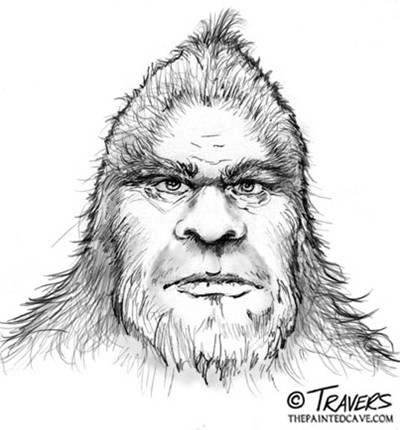

Face

The most obvious feature of the wood ape face is its relative flatness, clearly lacking the prominent snout of a bear. According to William Roe, the nose of the wood ape he saw was “broad and flat” but the lips and chin protruded farther than its nose. This slight prognathism (projection of the mouth or jaws) has been reported in other sightings. For example a hunter who watched a wood ape eat blueberries at the edge of a highway noted it had a humanlike face, “except for the protruding mouth.” One female motorist noted that the wood ape she saw in Newton County, Texas, 1986, had a face that was “flat like [that of] a human…not a pointed nose like a bear.”

Limb Proportions

It is frequently noted that, compared to a human, the wood ape has disproportionately long arms. William Roe, for example, noted that the arms of the wood ape he saw were “much thicker than a man’s arms, and longer, reaching almost to its knees.” This is reflected in his daughter’s drawing of the animal he observed, done under his direction.

Hair: Color, Length, and Distribution on Body

Hair Color

Although wood ape hair color is most often described as brown (light to dark), black, or simply “dark,” other colors have been reported. These include gray, light, white, and silver-tipped. Red (like a Hereford cow) and reddish-brown are also reported with a relatively high frequency. In Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana, reddish-brown is the second most frequently reported color, after black or dark.

Hair Length

One of the main field marks of the sasquatch is its hairy or fur-covered skin. The hairiness of bears is almost never remarked upon, presumably because hairiness is their natural and expected condition. The presence of hair on the wood ape, with its humanlike appearance and gait, seems to be more noteworthy. Hair length, as described in numerous reports, varies from short to long, and may appear smooth or shaggy. It is often longer on the head, shoulders, and arms than elsewhere on the body.

Distribution of Hair

Patches of bare black skin on the face and chest of wood apes are sometimes mentioned in reports where close observations have been made. A wood ape observed near Estacada, Oregon, in 1973 was covered with thick hair except on the throat and chest where the observer saw muscles and skin “the color of a sunburned man.” The young man mentioned earlier, near Jefferson, Texas, described the animal he saw at close range as having hair that appeared “dull and coarse.” He stated that its hair “covered most of the body, not including the face (with the exception of the cheeks and jawline), forehead, palms of the hands, and the hair appeared much thinner on the thoracic (chest) and abdominal regions.” The witness, who had a prolonged daytime view, described the skin as “somewhat tough and weathered,” and “medium toned (not black or brown).”

Anatomical Characteristics of Sex

Breasts in Females

The most obvious evidence of gender in wood apes are the visible breasts of some adult females, such as the one in the Patterson-Gimlin film, and their absence in males. Many observers, such as William Roe, have noted the presence of obvious, engorged breasts and, on this basis, identified the animal they saw as a female.

In most sightings where breasts are observed, they are described as “pendulous” or “long and droopy.” The female ape that Albert Ostman watched over a period of several days must have had this appearance, since he stated that “some of those lovable brassieres and uplifts would have been a great improvement on her looks and her figure.” In one report, a six-foot-tall wood ape was described as completely covered with shiny hair except for its face, hands, and the nipple area of its very large breasts. A 2004 sighting report from the Crockett National Forest in Texas had a hunter making a prolonged morning observation of two wood apes, apparently male and female, while they were “turning over fallen limbs and eating something from under them.” The hunter said of the female, ”’she’ had pronounced breasts…” A fisherman in Sebastian County, Arkansas, described the wood ape he saw in 1988 as having “what looked like large floppy breasts.”

Differences From Human Gait

The wood ape bipedal gait differs not only from the quadrupedal gait of other mammals but also from the human bipedal gait in several small but significant ways. Many observers have remarked on the gracefulness of the wood ape stride. One man likened the wood ape he saw to “a really fit athlete” as it strode off. A woman who watched a wood ape stride across a beach on the west coast of Vancouver Island in August, 1995 said it moved “as if it was walking on air,” and an Ohio observer watched a wood ape cross a field “taking strides as if it were walking on eggshells.” One Texas woman, while in the Sam Houston National Forest, in Walker County, Texas, 2005, described a wood ape she observed as moving “to the side of the road in a smooth motion.” She went on to say that its movement was “fluid—like it was floating.” Similarly a man who watched a wood ape near the Alaska Highway in the Yukon noted that its motion was smooth and “there was no bobbing movement at all.”

One may wonder just what it is about the wood ape gait that renders it so graceful. The Patterson-Gimlin film, despite its lack of visual detail, clearly shows the smooth, ground-eating strides of an adult wood ape walking along a sandbar. Several investigators, including professor Grover Krantz of the University of Washington, have examined this film at length. The results of his investigations show that the wood ape has a bent-knee gait wherein the knee does not lock during the stride as does the knee of humans. This bent-knee stride, which we humans employ in the diagonal stride of cross-country skiing and in fast ice-skating, lends fluidity and removes the vertical motion inherent in the normal human stride. At least one man who watched a wood ape walk away with a very smooth, rapid gait noticed this “peculiar” posture and observed that “its legs were always bent as if in a slouch.” A woman in Rogers County, Oklahoma, in 2002 described a wood ape that she observed as “somewhat stooped; it slowly swung its arms and had a slight knee bend.”

The arm-swing of the walking wood ape is also noteworthy. First, it is worth noting because it is present at all, and second, because it sometimes appears exaggerated when compared with the normal walking gait of humans. In the Patterson-Gimlin film, for example, the hand is raised high in front of the body, describing a longer arc than humans normally exhibit. In 2007, a security guard who reported a late night visual encounter with a wood ape near The Woodlands, in Montgomery County, Texas, remarked that it had an “odd arm swing,” and “had a very long unusual stride.” Todd Neiss, describing the three wood apes he observed near Seaside, Oregon, in April 1993 remarked on the “exaggerated arm movements” of the animals as they walked swiftly out of sight.

A less obvious difference is the tendency of the wood ape to pick up its feet at the end of a stride to a greater extent than humans normally do. Like the arm-swing, this action is an exaggeration of a normal human action, and brings the sole of the foot to an almost vertical position at the end of each stride.

Occasional Quadrupedal Gait

In the spring of 1996 an observer near Cambridge, Ohio, saw an adult wood ape with a four-foot-tall juvenile. The juvenile was “bouncing around like a chimpanzee” and “never did walk totally erect like the other one.” The situation in infant wood apes may be similar to that in humans in which young individuals take many months to “learn to walk” in the sense of mastering bipedal locomotion.

Although bipedalism appears to be the norm in adult wood apes, there are a few reports where quadrupedal locomotion was observed. The first, a historical report (1869) of a “wildman or a gorilla or ‘what-is-it’” from eastern Kansas and western Missouri, notes that the animal “generally walks on its hind legs but sometimes on all fours.” A more recent report from western Florida in 1975 describes two boys being chased by a “skunk ape that smelled terrible and ran on all fours in a crablike fashion as well as running upright.” A witness who, as a boy, observed a wood ape at close range in 1989 near Jefferson, in Marion County, Texas, remarked how the animal he saw was emerging from dense woods “moving on all fours” until it hoisted itself up using a nearby fence-post, transitioning smoothly into a bipedal posture and gait. The young man noted that the “change in gait or posture did not result in a change in its speed.” When the animal fled, it “took off sprinting on two legs, using his hands to tunnel his way through the thicket.”

Upright Stance and Hunched Posture

It should be noted that although wood apes stand and walk fully upright on two legs, they often assume a hunched posture. The hunched or stooped posture noted in many wood ape reports may have an anatomical basis. A.F. Dixson shows that whereas in humans the spine enters the base of the skull, in the gorilla it enters the rear of the skull. This configuration may be partly responsible for the apparent absence of a neck in the wood ape in front or rear view. It also restricts turning of the head so that the entire upper body must rotate in order for the animal to look sideways or rearward. This restricted head movement is visible in the Patterson-Gimlin film and has been discussed by Grover Krantz in Big Footprints.

When standing, wood apes may slouch with their long arms dangling. Occasionally they lean sideways against a tree using an extended arm for support.

Crouching, Squatting and Sitting

Crouching

Wood apes typically move about in a crouch or stooped position when foraging. For this reason they are frequently mistaken for bears until they stand erect or walk away bipedally. One example of this occurred in the spring of 1997 in British Columbia’s Fraser Canyon where a bear hunter watched what he thought was a bear through his rifle scope. While he was waiting for the “bear” to turn sideways so he could assess its size, the animal stood up on its hind feet, reached above its head, and with its hand pulled down the tip of a tree branch from which it ate the leaf buds. It took a step forward and repeated this process, still on its hind legs. By the time the animal stood erect the hunter realized he was not watching a bear, but a completely different animal. (In addition to its wide shoulders he observed bare skin on its flat face and on the sides of the chest below its arms.)

Squatting and Sitting.

When wood apes pause or rest they may squat, or sit on a stump or similar support. Squatting wood apes have also been reported in shallow water where they were apparently harvesting water plants with their hands, or on land, where they have been seen digging or handling roots with their hands.

Swimming

Swimming must be examined alongside the terrestrial gait of the wood ape since it appears to be an important means of locomotion throughout the range of this species in North America, especially on the west coast. Circumstantial evidence, such as reports of the presence of wood apes on small islands off the coast of British Columbia, has suggested they swim. Observations of wood apes actually swimming have confirmed this.

In a 1965 sighting on the northern British Columbia coast, a boatman saw a wood ape swimming towards a rocky islet on which two others were standing. “The one in the water swam very powerfully and very fast, with the water surging around its chest.”

There are at least two reports of wood apes swimming in large rivers. In Montana a wood ape was reported swimming from the west bank of the Missouri River to Taylor Island in August, 1976. And in Grand Rapids, Manitoba, nine members of a family saw a wood ape swim up the Saskatchewan River past their house and then come out and walk into the bush a quarter mile away.

In his book In the Big Thicket: On the Trail of the Wildman, Rob Riggs wrote of “Old Mossyback,” reportedly an “ape-like creature” that dwelt in and around the Trinity River of Southeast Texas. Riggs told of one particular man he interviewed named John who presumably saw “Old Mossyback” as it raided his rabbit pen and made off with one of the rabbits near Dayton, Texas. John pursued the “large, dark form,” staying just close enough to hear the terrified rabbit’s screams. John made it to the bank of the Trinity River and watched in the moonlight “a huge ape-like animal” as it swam to the other side of the river still holding onto the rabbit.

A Washington couple, fishing in the Nooksack River in September, 1970, saw a black eight-foot-tall, slightly-stooped animal with a flat face and no neck standing in water up to its knees about two hundred yards away. It bent down and disappeared in the muddy water. Later, tracks were found coming out of the water onto a sandbar for about 150 yards and then back into the river. (The tracks were thirteen-and-a-half inches long with a forty-five inch stride.) The wife saw the wood ape again later in the month when it stood up at the front of her boat in water about five feet deep which came only to the top of its legs. These sightings took place during a heavy salmon run; other wood ape sightings were made during the same period in the same area.

South of Lummi, Washington, not far from the above location, a young girl watched while a wood ape stood and swam off the beach in front of her house at dawn as fog was lifting. It seemed to be fishing.

Finally, from Ketchican, Alaska, there is a report of a fifteen-year-old boy who saw a humanlike figure standing waist-deep in the water between the float of a dock and the shore. When he screamed and fled, about thirty men came out of shock on the dock and saw the animal as it dove under water and swam away. Looking down they could see it swimming underwater with its arms forward and legs doing a frog-kick until it swam out of sight. Prior to this, these fishermen had been troubled with something ripping nets and stealing fish. This report is significant because it describes the stroke used by at least some wood apes when they swim.

Several of these reports suggest that swimming in wood apes not only serves as a means of locomotion for travel, but may be sufficiently developed to serve in catching fish.

References

Bindernagel, J. A. (1998). North America’s Great Ape: The Sasquatch. Beachcomber Books. Courtenay, B.C., Canada.

Crowe, Ray, ed. Newsletter of the Western Bigfoot Society. 225 Northeast 30th Avenue, Hillsboro, OR.

Dixson, A.F. (1981). The Natural History of the Gorilla. Columbia University Press, New York, NY.

Green, John. (1968). On the Track of the Sasquatch. Cheam Publishing, Ltd., Agassiz, B.C., Canada.

Green, John. (1973). The Sasquatch File. Cheam Publishing, Ltd., Agassiz, B.C., Canada.

Green, John. (1978). Sasquatch: the Apes Among Us. Cheam Publishing Co., Agassiz, B.C., Canada; Hancock House, Saanichton, B.C., Canada.

Keating, Don, ed. (1994 & 1996). Monthly Bigfoot Report. Eastern Ohio Bigfoot Investigation Center, Newcomerstown, OH.

Krantz, Grover. (1992). Big Footprints: a Scientific Enquiry into the Reality of Sasquatch. Johnson Books, Boulder, CO.

Riggs, Rob. (2001). In the Big Thicket: On the Trail of the Wildman. Paraview Press, New York, NY.

Steenburg, Thomas N. (1990). Sasquatch/Bigfoot: the Continuing Mystery. Hancock House, Saanichton, B.C., Canada.

Artwork created by Pete Travers.